Far beyond our eyes: microplastics at the bottom of the sea

- batepapocomnetuno

- 18 de jul. de 2024

- 6 min de leitura

By Gabriel Stefanelli Silva

English edit by Carla Elliff

When I started reading about plastic in the ocean, in the distant year of 2011, I was still at the beginning of my degree in marine biology. At that time, we already knew that there were large amounts of litter – and not just plastic – floating around. The existence of these concentrations of garbage in places where marine currents form large gyres had strong media coverage, with the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) being the largest concentration of marine garbage in the world. To give you an idea, the GPGP covers an area of approximately 1.6 million km², the size of the state of Amazonas! Can you imagine? Although many people think that these concentrations are islands of trash, they are actually a “soup” made up of various types of debris. Most of it is made up of microplastic, plastic particles that measure between 5 mm and 1 µm – sometimes you can't even see them with the naked eye! Located between California and Hawaii, the GPGP is so heterogeneous in its waste distribution that along its length we can find everything from a lot of litter to little or no litter at all. But despite being famous, the GPGP is just one of the points where marine litter accumulates – so where does the rest go?

Extent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP), between California and Hawaii. The figure shows that there are two “garbage gyres” in the Subtropical Convergence Zone. The western gyre is less extensive and is located near Japan.

(Source: NOAA Marine Debris Program, public domain)

Six years later, when I finished my master's degree on freshwater fish, I decided to return to my roots and delve deeper into marine litter in my doctoral project. I found an article published in 2016 about a group of British scientists led by Dr. Michelle Taylor (who continues to be a great reference in the field), about the first report of microplastic ingestion in deep-sea animals, and that made me very excited! I contacted Professor Paulo Sumida from the Oceanographic Institute of the University of São Paulo (IO - USP) and we started working on some ideas. Paulo's laboratory is the only one specialized in the deep sea in Brazil, and it seemed ideal to me to carry out a project on garbage in these very remote regions of the ocean. The deep sea, since it began to be studied at the end of the 19th century, is still a great place for exploration research! And when it comes to plastic waste, we see a lot floating on the surface, but we have very little idea about where it all ends up...

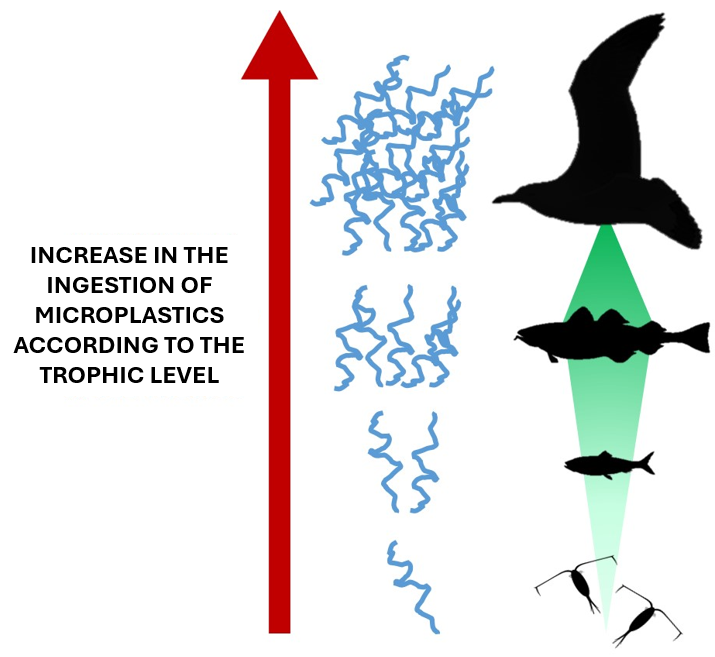

What we already know is that much of the material that floats on the surface ends up sinking due to the action of marine currents and the accumulation of microorganisms, which increase the density of particles. Eventually, this litter reaches the bottom sediment and becomes trapped between grains of mud and sand. This means that animals that feed on deposited material, such as sea cucumbers, and filter feeders, such as shellfish, are extremely susceptible to ingesting microplastics. Paulo and I then decided to carry out an analysis of the ingestion of this material along the deep-sea food web, checking whether a particle ingested by a given organism could be transferred to its predator, a phenomenon known as biomagnification. This means that animals at the base of the web (or at a lower trophic level), even though they are unable to ingest a large amount of microplastic, could cause an accumulation of waste in the digestive tracts of their predators when consumed in large numbers, and so on. When they die, top predator organisms could also return the microplastic to the environment and restart the process. Over time, these litter ingestion cycles become increasingly serious and more harmful to the ecosystem.

Microfiber (indicated by white arrows) found in shellfish.

(Source: photo by Paulo Ferraz, license CC 4.0 SA-BY)

Example of biomagnification of plastic microfibers (in blue) from the consumption of contaminated organisms along a marine food chain. From bottom to top, there is an increase in the trophic level of organisms, starting with zooplankton microcrustaceans, passing through fish and ending with a predatory bird.

(Source: Gabriel Stefanelli, license CC 4.0 SA-BY)

Working with the deep sea – and ocean research as a whole – can be challenging. Part of my doctorate involves scientific cruises, and my first onboard expedition was to a location more than a thousand kilometers off the coast of São Paulo. At the end of five days of travel, with violent seas (and a lot of vomiting), we had a problem with the nets and it was not even possible to collect any samples. Fortunately, there is always a plan B and today I already have material from other expeditions, including animals collected since the 1980s and which are part of the Prof. Edmundo F. Nonato Biological Collection of the Oceanographic Institute of the University of São Paulo. Putting together all the material I have available, there is more than 30 years of information about pollution in the ocean. Tricky, but very interesting!

Shelves of the Prof. Edmundo F. Nonato Biological Collection (ColBIO) from the

Oceanographic Institute of the University of São Paulo

(Source: photo by Gabriel Monteiro, license CC 4.0 SA-BY)

I'm almost halfway through my PhD, and fittingly almost half of the organisms I analyzed had at least one microfiber inside them. And while we wait for the university's activities to resume to analyze these microfibers, we continue to see news about marine pollution. Last month a study was published showing that plastic that has been lying on the seabed for more than 20 years remains preserved as new and provides an environment that is conducive to microorganisms that would not normally be in that area, which can pose major threats to the functioning of the deep-sea environment. Also recently, a new species of amphipod – a type of crustacean – was discovered from the deep sea that was collected with microplastic in its stomach. The species even received a symbolic name, Eurythenes plasticus, and is just another example of how the litter we produce reaches remote locations in the ocean, from the poles to the deepest regions of the planet. It really surprises me how plastic, especially in the form of micro and nano particles, is permeated in the marine environment, and that even the fish on the table in so many homes can be contaminated by a pollutant that we can't even see clearly! The times we live in seem truly desperate; is it possible to get something positive out of this situation?

Precisely because it is readily appealing, the topic of marine litter has promoted waves of mobilization for greater care for the environment. One of the recent pieces of evidence was the ban on plastic bags and straws here in São Paulo and in other states in Brazil. Among other initiatives, we also have a ban on single-use plastic items in Europe, projects to recover abandoned fishing nets in the USA, and strategies for youth participation in combating plastic pollution in Asia. This is the best time for discussions about the anthropogenic impact on nature, and we can’t leave this for later. It is now that we have the potential to change people's perception of how we are capable of altering – for worse or better – the environment, one microplastic at a time. Or, if we prefer, one less microplastic at a time!

Litter on a beach in São Vicente, coast of São Paulo. (Source: photo by Fernando De Grande, license CC 4.0 SA-BY)

Suggested complementary literature:

About the author:

I've been interested in the ocean (and the deep sea) since I was a child. I graduated in biology, completed a Master’s degree in ecology, and I am halfway towards a PhD in oceanography. My primary area of research is ecology, with a dash of pollution and ocean education and literacy activities. I'm a fan of Pokémon, I like to cook for my favorite environmentalist, and annoy Tapioca and Dominique, my cats. If you have any questions, comments or suggestions, you can send them to gabrielstefanelli@hotmail.com.

Comentários